2016 has begun with a fizzle. Markets have plummeted over 5% in the first couple of weeks and sentiment is dim. The perfect time to discuss shorting strategies. Shorting is selling stocks you don’t own. It’s a way to bet on something going down. The exact mechanics of a short is as follows. If I want to short shares of Apple, I will first have to find someone willing to lend me those shares. After I borrow the shares, I’ll sell them. When I’m finished with my bet, I will buy those shares back and return them to the person who lent them to me. If the price has gone down, I’d pay less to buy the shares back than when I sold them, making money. This sounds complicated, but in most brokerage accounts (short-selling requires brokerage accounts to be margin enabled), the process is pretty seamless and short-selling is as easy as selling a stock you own. Instead of a positive share count you see for stocks you’ve bought, short positions will show up as a negative share count.

So how do you decide what to short? It’s pretty much exactly the same as deciding what to buy, except you want things that have historically gone down in value. Think of criteria that were associated with future out-performance (low P/E ratios, small cap stocks, winning stocks, etc.) and flip them. For example, high P/E ratio stocks, or even better, stocks which negative earnings (the companies lose money) will generally do badly going forward. Large cap stocks will do badly compared to other stocks. Stocks that went down the past year will continue going down next year.

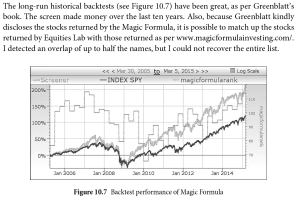

Here’s a screen that does these 3 things …

A hundred dollars invested in this screen goes down to about a quarter in last decade, while the market is up 80%. In the first 16 days of 2016, this screen has decline 15% (vs. the market’s 6-ish% decline). That means if you had been short $100 worth of the stocks that passed this screen on Jan 1st (or Jan 4th, the first trading day) you’d be up $15!

Disclaimer: Short selling has significant risks. Unlike a long position, where the most you can lose is your original investment (if the stock you bought ends up worthless), in a short position, your potential loss is theoretically infinite as a stock price could keep increasing forever. People betting against Netflix over the last few years found this out the hard way … Short with caution.